Saturday, September 30, 2006

Fighting Irish Restoring South Side of Chicago

Come on down for a presentation by Mr. Heyer on HJ Schlacks.

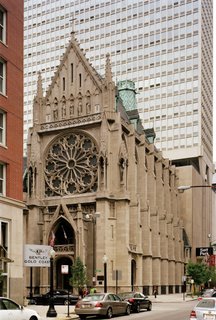

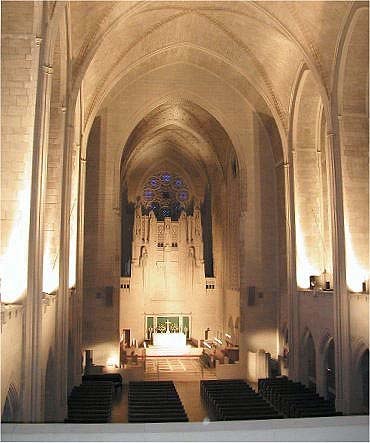

Rome to Chicago: The Classical Patrimony in Churches of Henry J. Schlacks

On Sunday, October 22th at 3:00 pm, there will be a conference by classical architect William C. Heyer on Henry J. Schlacks within the vast space of one of his neo-Renaissance masterpieces -- the historic landmark once known as “St. Clara Church” in south-side Chicago. This magnificent lime stone edifice was built in 1923-27 and was home to a thriving church community. Eventually closed in 2002 and scheduled for demolition, the building will now be fully restored by the Institute of Christ the King Sovereign Priest, following early Baroque Roman models for its interior.

Architect Henry J. Schlacks was one of the leading figures in the late 19th and early 20th century historicist Revival movement in architecture, designing many of the magnificent churches in Chicago. Schlacks traveled extensively in Europe, carefully studying the great and lesser known masterpieces of architecture of the old continent and applying this knowledge to his many works in the city. Among these is the former St. Clara in the south-side, now a historic landmark renamed as the Shrine of Christ the King Sovereign Priest.

Mr. William C. Heyer graduated summa cum laude from Pratt Institute in New York City, and after apprenticing with Thomas Gordon Smith, founder of the classical architecture program at the University of Notre Dame, obtained his Master’s degree from the same university, having conducted part of his graduate work in Rome. He has worked in classical studios in New York City, Washington, DC, and in 2002 founded his own classical architecture studio in Columbus; he is the architect assigned to the restoration of the Shrine of Christ the King Sovereign Priest. Mr. Heyer has written in Sacred Architecture Journal, Period Homes Magazine, and Culture Wars magazine, as well as The Latin Mass magazine.

The lecture will take place on Sunday, October 22th at 3:00 pm at the Shrine of Christ the King Sovereign Priest, and a reception will follow. 6401 S. Woodlawn Avenue, Chicago, Illinois, 60637. Parking is available in the adjacent parking lot. Take Lake Shore Drive to Hayes Drive/63rd Street, then 1.5 miles west to Woodlawn.

For more information and to register call 773-363-7409.

Wednesday, September 27, 2006

Meeting with Cardinal Arrinze in Rome

From Rome

Add this to any believe it or not file you may be keeping. I was blessed to present the Society of St. Barbara to his Eminence, Cardinal Arrinze, head of the Vatican Office of Divine Worship on Sunday Evening. The Cardinal showed a great interest in Traditional Architecture, the Liturgy, and in keeping Churches in tact.

The Cardinal is in correspondence with the Society of St. John Cantius, the Liturgical Institute, and Notre Dame concerning ecclesiology, and was very supportive of the efforts of SSB to restore the sacred nature of church architecture.

I promised not to post personal photos, but in this exception, here is Fr. Robert Sirico, Cardinal Arrinze, and John Powers, in a photo by Kris Mauren.

Tuesday, September 19, 2006

Quigley Preparatory Seminary to Close

This from the Archdiocese of Chicago:

After much deliberation and consultation with a committee of official representatives, including the rectors of our various seminary systems, Francis Cardinal George, O.M.I. has approved the recommendation to close Archbishop Quigley Preparatory Seminary High School in Chicago. Quigley will close at the end of this academic year on June 15, 2007.

For the last 101 years, Quigley Seminary has served the Archdiocese of Chicago by teaching thousands of young men to keep the Word of God alive in their hearts and their minds while preparing for their life choice in the seminary system or as good, Catholic laymen who have gone on to serve the Church, the community and the nation.

The changing patterns of vocation discernment has had a great impact in the ability to maintain a high school seminary program. For many years Quigley has been one of the few high school seminary preparatory schools in the United States. Declining numbers of students, along with growing costs per student associated with operating Quigley, have also led to this difficult but necessary decision.

It is the intention of the Archdiocesan leadership to continue to find new ways to help young people in the Archdiocese of Chicago listen for God’s call to the priesthood and religious life.

The historic Quigley buildings at 103 East Chestnut will undergo a year-long remodeling and restoration project and will become the new home of the Archdiocese of Chicago Pastoral Center.

The Society of St. Barbara requests your prayers (to the Lord) and suggestions (to the hierarchy) that the public continue to enjoy access to the Zachary Taylor Davis/Joseph McCarthy Masterpiece, and that the Archdiocese renews its commitment to high level classical education by other means than Quigley at the end of its glorious service.

Saturday, September 16, 2006

The San Gennaro Festival, New York City

Though I do have to wonder--why does one festival require ten identical sausage-and-zeppole stands, two identical perfume-selling booths? Or, more to the point, are there any funnel-cake sellers left east of the Hudson who are not at Mulberry Street right now?

The Madonna in the forecourt of Precious Blood Church.

Modern-day firsfruits.

The saint of the day.

Can Grande.

Cavallo piccolo.

Thursday, September 14, 2006

The San Rocco Festival, New York City

My first introduction to the cultus of San Rocco came, through, of all things, a screening of The Godfather II. A close friend of mine had been so taken with the scene where young Don Corleone rubs out...well, I honestly can't remember who was shooting who, or whether it was before or after they ended up stealing that sofa from Fanucci's house, but the point was, the tenement murder was juxtaposed against the procession outside, profane blood against the sacred, gunshots muffled by celebratory firecrackers. As a consequence, San Rocco and his procession have since been surrounded by a strange and holy halo in my mind, a primal, earthy good full of the sun and grapes of Italy that will forever justify and counteract whatever petty violence crops up in a culture.

Also, it's hard not to remember the supremely odd and rather oddly wonderful image of a gilded, wooden saint cloaked in a feathery fringe of a hundred dollar bills, one of those apparently inexplicable but somehow significant bits of folk-Catholicism that so impress themselves on the mind.

The word earthy is particularly appropriate here--and the Frenchman Roque's feast comes from the Italian earth of Potenza, where, as San Rocco, he is highly venerated. His spiritual children brought him and the festival with them across the sea to the new world, a rooted, organic presence to turn to in the grime, confusion, smoke and steel of the New World. He is popular--as in the sense of in the people, and his festival is full of the popular enthusiasm and deep-rooted and God-given spiritual cravings that humanity can only manifest, can only express and attempt to satiate through the medium of the physical. It's the sort of impulse that some might call pagan, and indeed it was prefigured in some pale way by the dim, smoking sanctuaries of the Greeks and Romans, but it reaches its ultimate apotheosis and justification in the Christian ideal, the redemption of the physical that is the Incarnation.

San Rocco's feast is a commemoration of the long-suffering saint's life, of his pilgrimage, his plague-wound, and his anonymous, humble death, but it is also an opportunity to present the first-fruits of the harvest to God. There are the dollar-bills--an ancestral muscle-memory of the days when San Rocco might have been garlanded with wheat and grapes, something that an outsider might condemn in five seconds as idolatry, but in five minutes makes perfect sense. And then, as we processed around, I realized that every time we stopped in front of a restaurant, a mortician's, another restaurant and deli, we stopped and turned the statue around with a florish of Little-Italy brass and clapping and "Viva San Rocco!" each proprietor had put an elegant display out along the processional route of all his produce--a dinner-plate of pasta, plastic-wrapped, bottles of wine, glasses, slices of mozzerella, as an ex-voto of thanks for another good year, passed on to God via his saint Rocco. A literal mind might condemn this as a superstition, seeing only its physical form, but the Italians and Italian-Americans are too forthright and sensible not to see its true spiritual significance.

Prayer is a sacrifice of time, a superfluous and "excessive" act--just as is the gift of a bushel of grain or a sack of flower to the cultus of a saint who would seem to have no immediate use for it. Like the Magdalene and her jar of perfume, sweetening the feet of Christ for the sake of sacred excess.

An Aside on Gothic Deco

I recently visited the Cathedral of Mary Our Queen in Baltimore with the Sober Sophomore as my fearless tourguide, as well as checking out the the old neoclassical Basilica from the outside; it won't be re-opened until after they're finished re-Latrobizing its plesantly stoic interior. (My initial reaction is that it looks too clean and will probably be much more agreeable when twenty years of exhaust fumes have mellowed it a bit).

The tympanum of the front portal of Mary our Queen, Baltimore.

The new Cathedral is an example of a peculiar and once peculiarly popular style, a sort of hard-edged deco take on Gothic which has a way of turning up in odd corners of the U.S. It can vary from the sculptor merely giving a certain chilly Works Progress Administration look to the figures as at Atlanta Cathedral, or a full-blown and surprisingly stripped-down skyscraper aesthetic, like that at, of all places, the cathedral in bucolic La Crosse, Wisconsin. Sometimes, the effect is kitschy Busby Berkeley, but more often than not, it can be quite striking, if one gives it an honest chance.

Christ the King, Atlanta. A strangely small cathedral of a cold sort of gothic, but not without a certain appeal.

While not as satisfying to me as more ornate and historically-minded forms of less radical takes on Gothic, these projects are nonetheless worthy of our consideration, both as period pieces and also as a fascinating lesson in architectural design both pro and con. Chicago has a disproportionately large number of them, as well as deco-izing forays into Romanesque and other styles, and almost all manage to convince as pieces of appropriately well-balanced work, not dependent on novelty but very competent expansions of the tradition down various side-paths otherwise ignored today. It is a bit on the modern side (and that opens a whole other field of questions I've not yet examined), but it is by no stretch of the imagination modernist.

The high rise was a favorite structure to Gothicize at the turn of the last century, and some of that verticality crept into the funkier turns of some of the other takes on modernity--deco, streamline moderne, and various simplified forms of classicism--that have since ended up getting lost in the historical-architectural shuffle. Deco has always struck me as a modern style which fits in more clearly inside the classical tradition, considering its interest in an ornamental language and iconography, and an external expression more in keeping with the traditional past. And while art moderne curves and portholes can be overdone, they have a sort of intriguingly low-key sense of geometric invention which appeals to my baroque side.

At the very least, they're better than glass boxes, and not without a certain charm, even if a whole city block in that manner would undoubtedly overwhealm. In a sense, we can term the more historicizing turns of these styles as a sort of subconscious "classical survival," just as some have spoken of a "gothic survival" that ran under the radar in Renaissance and baroque days. Most architects of the time considered themselves very modern, no doubt, but the subsequent spectrum-skewing weirdness of Eisenmann and Gehry virtually makes them honorary classicists. Certainly churches like Mary Our Queen are Gothic Revival Survival, and, as an organic link to the past (or the closes thing at present), worth our consideration and time.

Cram's most unusual take on the modern is Pittsburgh's East Liberty Presbyterian, with a crossing-tower derived from reverse-engineering the Empire State Building into a Gothic milieu. The result is exotic and rather appealing.

If I may be permitted an aside, it is interesting to note that Cram himself, the premier neo-Gothicist of our age, was quite enamored of skyscrapers and his work got uncharacteristically stark in his twilight years. He himself seems to have made little distinction between deco and what is now simply called Modernism despite the deco tendencies in his late work--which I would argue was less irritatingly revolutionary than he thought. And I mean that as a compiment.

Being experimental, Gothic Deco never quite reached the perfection of a polished style, and may vary from deco modernism dressed up in a thin layer of Gothic--sometimes fun, sometimes mildly silly, and not quite properly ecclesial--to a fully-thought-out and coherent synthesis. In these better examples it is perhaps more useful to consider it not necessarily merely a "modernized" Gothic (even if its makers thought so) but a Gothic of a chunkier, more masculine aspect, avoiding chronological snobbery, either of a historicist or modernist slant. It is not the only "modern" approach to Gothic, as the historical treasure-trove of the period still offers much exploration without necessarily injecting a deco element; at the same time, it is a fascinating approach to this manner of design.

The two best examples of the style are the most strongly synthesized, and are simultaneously the most vigorously hefty and the most Gothic at once. One of them is just a few blocks away from my apartment. I walked by there one afternoon under a dirty pearl-grey sky with the smell of ozone in the air. It's the Episcopalian Church of the Heavenly Rest, a massive and yet surprisingly vertical structure which succeeds in mingling Romanesque mass with Gothic vigor. Something about its fluted spires suggest living rock, or the facets of a spiky crystal, and indeed a few of the blockiest bits on the side indicate bits that never got carved.

The Church of the Heavenly Rest, New York City: a curious but successful blending of chunky Deco and turn-of-the century Gothic.

It's not a church that work work everywhere, of course. It is a stunning piece of work, though one that would best thrive amid the hefty towers of a high-rise city. It is the answer to a very specific architectural and theological question, but it seems to me the right answer in this instance. I could perhaps see some of this approach working in a church dedicated to some military martyr, to St. George, for instance, though somehow the curious titulus of Heavenly Rest suggests a more delicately vegetal art-nouveau evocation of Gothic to my mind. The sculptural program continues this blocky deco trend; it works in the context, but I wonder if perhaps the vigor of the building might not have been more improved had we seen more delicate angelic visages rising from rough-hewn folds in the manner of the cowled tower guardians of Goodhue's St. Vincent's. Still, it holds its own well against its often inhospitable urban surroundings.

The Heavenly Rest from the outside, from across the street at Central Park. Like all good city churches, it dominates in spite of its surroundings.

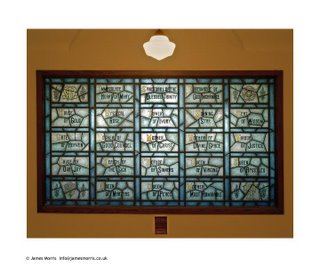

The second, Queen of All Saints Basilica, stands in Chicago, and is notable for the extremely late date of its completion, 1959. It may well have one of the the last tradition-minded churches built in America until the present revival, and is of a Gothic which has a distinctly twentieth-century feel to it, but at no sacrifice to its iconography, beauty or craftsmanship, or its ability to be taken seriously. It is modern, but not irritatingly or faddishly so. Indeed, its iconographic scheme is a fine example of the (old) Liturgical Movement's concept of "anticipated eschatology"--an iconographic program which serves to highlight the earthly Mass by its representation of the heavenly liturgy. Though the mural behind the altar, of the Trinity in a burst of glory, placed in conjunction with the spire of the reredos, looks a little too much like a graphic of a '30s radio tower to not incite some small amusement in me.

Queen of All Saints Basilica, Chicago, completed at the astonishingly late date of 1959.

Then there is La Crosse Cathedral, which occupies the opposite side of the spectrum in being more modern than it is Gothic, but nonetheless it manages to preserve a convincing sense of liturgical hierarchy. Architecturally, it's rather cold, but it remains a fascinating period piece. Its sanctuary, spacious and broad with numerous choirstalls and a freestanding altar meant to be used ad orientem, is a model of how a cathedral's chancel should be built (though it could use a big crucifix as a focus), while one of its side chapels, dark, atmospheric and vaulted in black-and-gold is a surprising find indeed for this forgotten and pleasantly real little town. The aesthetic is a bit too stripped, and the distinction between walls and vault somewhat lost in the process, while the vast facade is of a startling blankness which succeeds in impressing more by its size and contrast to surroundings than its intrinsic qualities. The outline is striking, but could bear a bit more filling in. It could get dull after a few days. That being said, photos I've seen of the Bishop's chapel are nothing short of wonderful, and very clearly designed by someone who knew the Tridentine rite well.

St. Joseph the Workman, La Crosse, Wisconsin. A brooding, stark sort of abstract Gothic; interesting forms in need of some more development.

And then there is Mary Our Queen. Like La Crosse, the interior is more striking than the exterior--indeed, I find the exterior more than a little strange, too reminiscent of the government office building where my father works, down in Florida. It is also a bit less abstracted than La Crosse, if not as studied in its details as the Heavenly Rest. The lines of its nave are most striking and noble in their loftiness, and austere but in a way that doesn't suggest their decoration was undercooked somehow. The high side-aisles continue the tradition established at St. John the Divine by Cram, itself begun as a response to the peculiarities of the site and project, of going virtually all the way to the vault of the nave, producing a pleasantly airy affect distinctly Gothic in spirit.

Mary Our Queen, Baltimore; a late work by Maginnis and Walsh, the architects of the Basilica in Washington.

Spots of elegantly executed polychromy brighten vaults and rafters not unlike Queen of All Saints. Many of the side-altars, tympana and the baldachino are, while very deco in inspiration, are nonetheless astonishingly well-crafted and quite intelligent in their iconography and their liturgical layout, especially considering the late date the project was undertaken. It would be instructive to compare it with another modern-historical hybrid of the same era and place, the massive National Shrine in DC. I've heard every conceivable opinion about the place, from undying devotion to unalloyed hatred, but that's a topic for another day, too.

Lady Chapel, Mary Our Queen. A striking bit of liturgical sculpture. This photograph does not include the curious five-sided tester canopy above.

I've got broad tastes, I admit, but I also find it instructive to consider the pros and cons of every work I enjoy. The vigor of Gothic Deco is the strength, and quite apparent, but the con is that in many cases, the architect was trying a bit too hard to be unique. It is good to strive for innovation within the tradition, but pushing an idea too hard can really ruin it. Better to use a tried-and-true formula if you're not quite sure. In some instances, the inherent angularity provides an interesting new spin on Gothic attenuation, but not everything, especially when it comes to statuary, has to be hard-edged, neo-primitive, over-stylized. As with much art, and much of my favorite work by painters such as van Eyck, the right balance between nature and symbol is the key to successfully expressing the Divine. Now that the flush of novelty has long worn off, it is possible to reconsider such choices, and the whole movement, with the luxuriantly long hindsight of tradition.

Tuesday, September 12, 2006

Barat Reprieved! Simony Thwarted.

The Lake Forest Preservation Council has stopped demolition of the Chapel of Convent of the Sacred Heart at Barat College. Thanks to all that have assisted in the preservation of the chapel in their research, testimony, prayers, and general belligerence.

It is still possible for the Lake Forest City Council to overturn the Preservation ruling, but the momentum is against destruction and in favor of maintaining the Chapel as a community space.

Shall we celebrate with The Litany of Mary?

Monday, September 11, 2006

Celebrated Author to Show Churches

Denis McNamara, the author of Heavenly City, will be giving a series of lectures this autumn. Denis gives a fine presentation and is a great tour guide. Come see a Founder of the Society of St. Barbara at:

Wed 9/13: Serra Club talk, Oak Park

Tuesday 10/10: Tour of Chicago's great churches with Miles Jesu

Monday 10/16: Tour of Chicago's Basilicas with Lumen Cordium Society

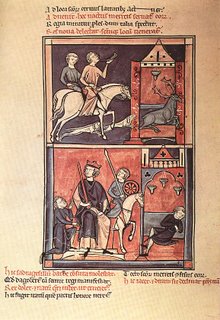

And the image? A tapesty of the life of St. Denis, of course.

St. Peter's Church New York City

In Remembrance:

"The body of the Rev. Mychal F. Judge offically the first casualty at the World Trade Center was brought to St. Peter's by firefighters on September 11, 2001 and laid before the altar"

In David W. Dunlap's "From Abyssinian to Zion"

Friday, September 08, 2006

Classical Church Architect Named to Top Post

From the Wall Street Journal:

The federal agency that builds courthouses, border stations and other federal buildings is set to name a new chief architect, a move that could usher in a return to a more traditional type of architecture in the government's $10 billion construction program.

The General Services Administration has selected Thomas Gordon Smith, an architect based in South Bend, Ind., according to several people who have been informed of the decision.

Mr. Smith is best known as a practitioner and promoter of traditional architecture that finds inspiration in Roman temples and palaces. His portfolio includes religious buildings in the Midwest, homes and the renovation of a building at the University of Notre Dame, where he served as chairman of the architecture school from 1989 to 1998. Mr. Smith said he is "delighted" about the appointment, but declined to comment further until the GSA makes an official announcement. A GSA spokeswoman declined to confirm the appointment.

The chief architect office is considered one of the most prestigious positions in the field of building design. It will oversee $1.6 billion of construction this fiscal year and has a long-range plan that includes around $10 billion of projects. Federal buildings are often the most prominent in town.

The previous chief architect, Edward A. Feiner, retired in January 2005, and the position has remained unfilled since. Through his "design excellence" program, Mr. Feiner recruited prominent as well as cutting-edge architects, including Richard Meier, Thom Mayne and Robert A.M. Stern. Mr. Feiner, now with architecture firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, declined to comment.

Many, though not all, of the projects under Mr. Feiner eschewed the classical tradition of white marble and columns common in pre-World War II federal architecture. In its place are buildings such as Mr. Mayne's futuristic San Francisco Federal Building, a metal-clad rectangular structure.

Mr. Stern, dean of the Yale School of Architecture and well known for embracing classical architectural traditions while tolerating modern ones, called Mr. Smith "a wonderful choice," though one that will "probably get a lot of people crazy." He says Mr. Smith has "a strong point of view, and that's great." Mr. Stern adds, "But he has the capacity to shift and manage his position without closing the door to others."

Others are worried federal architecture will lose its cutting-edge focus. Henry Smith-Miller, of Smith-Miller + Hawkinson, a New York firm, which designed a border station under construction in Champlain, N.Y., said he finds Mr. Smith's appointment "deeply troubling." He called Mr. Smith's traditional views "anti-progressive." It "picks up the imperial nature of Roman architecture, which was in service to the empire rather than service to democracy," says Mr. Smith-Miller.

Wednesday, September 06, 2006

It must be: Eugene Liebert

What should a classic prep school have for buildings?

Let's see, ivy-covered bricks, beautiful gothic architecture, a serene chapel with stunning stained glass windows and a coffeted ceiling, it could only be the Indian Community School of Milwaukee (and you were thinking St. Albans!), right in the heart of urban capital of Germanic Architecture in the USA.

The former Concordia College a Lutheran "synods finest educational institution" in its day, was built in 1900 by my current study, Eugene Liebert, the teutonic master. I have become so taken with Liebert's buildings that I drove up to Milwaukee today to search a few out, and was lucky enough to be welcomed by Jim Laux, the facilities manager, to the Indian Community School of Milwaukee.

Now supported by the Pottawatamie Tribe, the school is busy and well attended. Many fine buildings adorn the campus. The "Old Main" from Concordia is no longer in use, but its structure is in fine condition, and looks ready to be used again.

Three cheers for Eugene Liebert!