Originally Posted on The Shrine of the Holy WhappingI recently visited the

Cathedral of Mary Our Queen in Baltimore with the

Sober Sophomore as my fearless tourguide, as well as checking out the the old neoclassical Basilica from the outside; it won't be re-opened until after they're finished re-Latrobizing its plesantly stoic interior. (My initial reaction is that it looks too clean and will probably be much more agreeable when twenty years of exhaust fumes have mellowed it a bit).

The tympanum of the front portal of Mary our Queen, Baltimore.

The tympanum of the front portal of Mary our Queen, Baltimore.The new Cathedral is an example of a peculiar and once peculiarly popular style, a sort of hard-edged deco take on Gothic which has a way of turning up in odd corners of the U.S. It can vary from the sculptor merely giving a certain chilly Works Progress Administration look to the figures as at Atlanta Cathedral, or a full-blown and surprisingly stripped-down skyscraper aesthetic, like that at, of all places, the cathedral in bucolic La Crosse, Wisconsin. Sometimes, the effect is kitschy Busby Berkeley, but more often than not, it can be quite striking, if one gives it an honest chance.

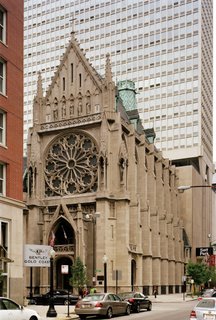

Christ the King, Atlanta. A strangely small cathedral of a cold sort of gothic, but not without a certain appeal.

Christ the King, Atlanta. A strangely small cathedral of a cold sort of gothic, but not without a certain appeal.While not as satisfying to me as more ornate and historically-minded forms of less radical takes on Gothic, these projects are nonetheless worthy of our consideration, both as period pieces and also as a fascinating lesson in architectural design both pro and con. Chicago has a disproportionately large number of them, as well as deco-izing forays into Romanesque and other styles, and almost all manage to convince as pieces of appropriately well-balanced work, not dependent on novelty but very competent expansions of the tradition down various side-paths otherwise ignored today. It is a bit on the modern side (and that opens a whole other field of questions I've not yet examined), but it is by no stretch of the imagination

modernist.

The high rise was a favorite structure to Gothicize at the turn of the last century, and some of that verticality crept into the funkier turns of some of the other takes on modernity--deco, streamline moderne, and various simplified forms of classicism--that have since ended up getting lost in the historical-architectural shuffle. Deco has always struck me as a modern style which fits in more clearly inside the classical tradition, considering its interest in an ornamental language and iconography, and an external expression more in keeping with the traditional past. And while art moderne curves and portholes can be overdone, they have a sort of intriguingly low-key sense of geometric invention which appeals to my baroque side.

At the very least, they're better than glass boxes, and not without a certain charm, even if a whole city block in that manner would undoubtedly overwhealm. In a sense, we can term the more historicizing turns of these styles as a sort of subconscious "classical survival," just as some have spoken of a "gothic survival" that ran under the radar in Renaissance and baroque days. Most architects of the time considered themselves very modern, no doubt, but the subsequent spectrum-skewing weirdness of Eisenmann and Gehry virtually makes them honorary classicists. Certainly churches like Mary Our Queen are Gothic Revival Survival, and, as an organic link to the past (or the closes thing at present), worth our consideration and time.

Cram's most unusual take on the modern is Pittsburgh's East Liberty Presbyterian, with a crossing-tower derived from reverse-engineering the Empire State Building into a Gothic milieu. The result is exotic and rather appealing.

Cram's most unusual take on the modern is Pittsburgh's East Liberty Presbyterian, with a crossing-tower derived from reverse-engineering the Empire State Building into a Gothic milieu. The result is exotic and rather appealing.If I may be permitted an aside, it is interesting to note that Cram himself, the premier neo-Gothicist of our age, was quite enamored of skyscrapers and his work got uncharacteristically stark in his twilight years. He himself seems to have made little distinction between deco and what is now simply called Modernism despite the deco tendencies in his late work--which I would argue was less irritatingly revolutionary than he thought. And I mean that as a compiment.

Being experimental, Gothic Deco never quite reached the perfection of a polished style, and may vary from deco modernism dressed up in a thin layer of Gothic--sometimes fun, sometimes mildly silly, and not quite properly ecclesial--to a fully-thought-out and coherent synthesis. In these better examples it is perhaps more useful to consider it not necessarily merely a "modernized" Gothic (even if its makers thought so) but a Gothic of a chunkier, more masculine aspect, avoiding chronological snobbery, either of a historicist or modernist slant. It is not the only "modern" approach to Gothic, as the historical treasure-trove of the period still offers much exploration without necessarily injecting a deco element; at the same time, it is a fascinating approach to this manner of design.

The two best examples of the style are the most strongly synthesized, and are simultaneously the most vigorously hefty and the most Gothic at once. One of them is just a few blocks away from my apartment. I walked by there one afternoon under a dirty pearl-grey sky with the smell of ozone in the air. It's the Episcopalian Church of the Heavenly Rest, a massive and yet surprisingly vertical structure which succeeds in mingling Romanesque mass with Gothic vigor. Something about its fluted spires suggest living rock, or the facets of a spiky crystal, and indeed a few of the blockiest bits on the side indicate bits that never got carved.

The Church of the Heavenly Rest, New York City: a curious but successful blending of chunky Deco and turn-of-the century Gothic.

The Church of the Heavenly Rest, New York City: a curious but successful blending of chunky Deco and turn-of-the century Gothic. It's not a church that work work everywhere, of course. It is a stunning piece of work, though one that would best thrive amid the hefty towers of a high-rise city. It is the answer to a very specific architectural and theological question, but it seems to me the right answer in this instance. I could perhaps see some of this approach working in a church dedicated to some military martyr, to St. George, for instance, though somehow the curious

titulus of Heavenly Rest suggests a more delicately vegetal

art-nouveau evocation of Gothic to my mind. The sculptural program continues this blocky deco trend; it works in the context, but I wonder if perhaps the vigor of the building might not have been more improved had we seen more delicate angelic visages rising from rough-hewn folds in the manner of the cowled tower guardians of Goodhue's St. Vincent's. Still, it holds its own well against its often inhospitable urban surroundings.

The Heavenly Rest from the outside, from across the street at Central Park. Like all good city churches, it dominates in spite of its surroundings.

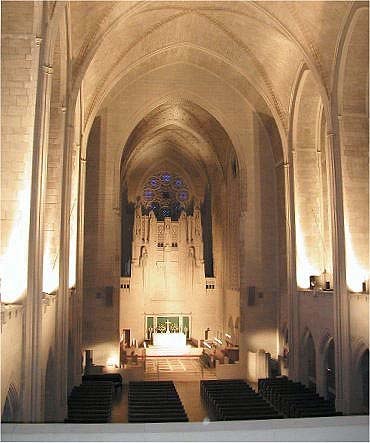

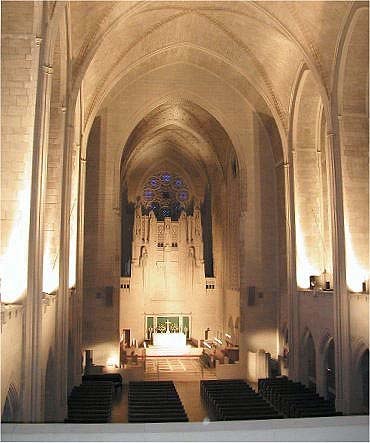

The Heavenly Rest from the outside, from across the street at Central Park. Like all good city churches, it dominates in spite of its surroundings.The second, Queen of All Saints Basilica, stands in Chicago, and is notable for the extremely late date of its completion, 1959. It may well have one of the the last tradition-minded churches built in America until the present revival, and is of a Gothic which has a distinctly twentieth-century feel to it, but at no sacrifice to its iconography, beauty or craftsmanship, or its ability to be taken seriously. It is modern, but not irritatingly or faddishly so. Indeed, its iconographic scheme is a fine example of the (old) Liturgical Movement's concept of "anticipated eschatology"--an iconographic program which serves to highlight the earthly Mass by its representation of the heavenly liturgy. Though the mural behind the altar, of the Trinity in a burst of glory, placed in conjunction with the spire of the reredos, looks a little too much like a graphic of a '30s radio tower to not incite some small amusement in me.

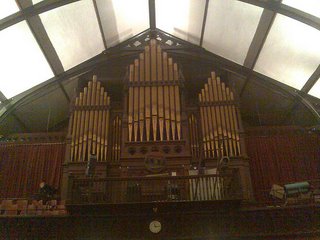

Queen of All Saints Basilica, Chicago, completed at the astonishingly late date of 1959.

Queen of All Saints Basilica, Chicago, completed at the astonishingly late date of 1959.Then there is La Crosse Cathedral, which occupies the opposite side of the spectrum in being more modern than it is Gothic, but nonetheless it manages to preserve a convincing sense of liturgical hierarchy. Architecturally, it's rather cold, but it remains a fascinating period piece. Its sanctuary, spacious and broad with numerous choirstalls and a freestanding altar meant to be used

ad orientem, is a model of how a cathedral's chancel should be built (though it could use a big crucifix as a focus), while one of its side chapels, dark, atmospheric and vaulted in black-and-gold is a surprising find indeed for this forgotten and pleasantly real little town. The aesthetic is a bit too stripped, and the distinction between walls and vault somewhat lost in the process, while the vast facade is of a startling blankness which succeeds in impressing more by its size and contrast to surroundings than its intrinsic qualities. The outline is striking, but could bear a bit more filling in. It could get dull after a few days. That being said, photos I've seen of the Bishop's chapel are nothing short of wonderful, and very clearly designed by someone who knew the Tridentine rite well.

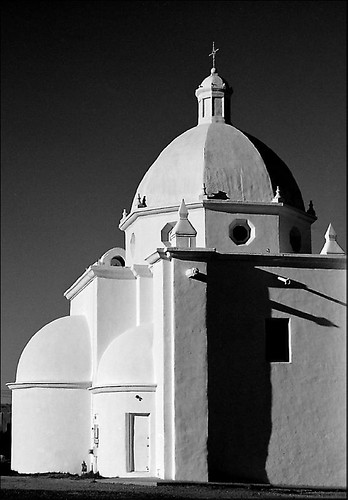

St. Joseph the Workman, La Crosse, Wisconsin. A brooding, stark sort of abstract Gothic; interesting forms in need of some more development.

St. Joseph the Workman, La Crosse, Wisconsin. A brooding, stark sort of abstract Gothic; interesting forms in need of some more development.And then there is Mary Our Queen. Like La Crosse, the interior is more striking than the exterior--indeed, I find the exterior more than a little strange, too reminiscent of the government office building where my father works, down in Florida. It is also a bit less abstracted than La Crosse, if not as studied in its details as the Heavenly Rest. The lines of its nave are most striking and noble in their loftiness, and austere but in a way that doesn't suggest their decoration was undercooked somehow. The high side-aisles continue the tradition established at St. John the Divine by Cram, itself begun as a response to the peculiarities of the site and project, of going virtually all the way to the vault of the nave, producing a pleasantly airy affect distinctly Gothic in spirit.

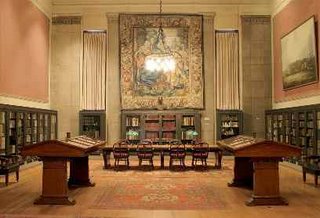

Mary Our Queen, Baltimore; a late work by Maginnis and Walsh, the architects of the Basilica in Washington.

Mary Our Queen, Baltimore; a late work by Maginnis and Walsh, the architects of the Basilica in Washington.Spots of elegantly executed polychromy brighten vaults and rafters not unlike Queen of All Saints. Many of the side-altars, tympana and the baldachino are, while very deco in inspiration, are nonetheless astonishingly well-crafted and quite intelligent in their iconography and their liturgical layout, especially considering the late date the project was undertaken. It would be instructive to compare it with another modern-historical hybrid of the same era and place, the massive National Shrine in DC. I've heard every conceivable opinion about the place, from undying devotion to unalloyed hatred, but that's a topic for another day, too.

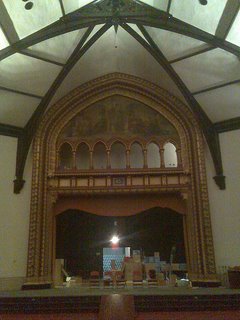

Lady Chapel, Mary Our Queen. A striking bit of liturgical sculpture. This photograph does not include the curious five-sided tester canopy above.

Lady Chapel, Mary Our Queen. A striking bit of liturgical sculpture. This photograph does not include the curious five-sided tester canopy above. I've got broad tastes, I admit, but I also find it instructive to consider the pros and cons of every work I enjoy. The vigor of Gothic Deco is the strength, and quite apparent, but the con is that in many cases, the architect was

trying a bit too hard to be unique. It is good to strive for innovation within the tradition, but pushing an idea too hard can really ruin it. Better to use a tried-and-true formula if you're not quite sure. In some instances, the inherent angularity provides an interesting new spin on Gothic attenuation, but not everything, especially when it comes to statuary, has to be hard-edged, neo-primitive, over-stylized. As with much art, and much of my favorite work by painters such as van Eyck, the right balance between nature and symbol is the key to successfully expressing the Divine. Now that the flush of novelty has long worn off, it is possible to reconsider such choices, and the whole movement, with the luxuriantly long hindsight of tradition.